Aberdeen History alum Julia Vallius has created a Working List to identify information about people who were witnesses or affixed their wax seals to many of the charters of the Aberdeen Carmelite friars from 1338 to 1431.

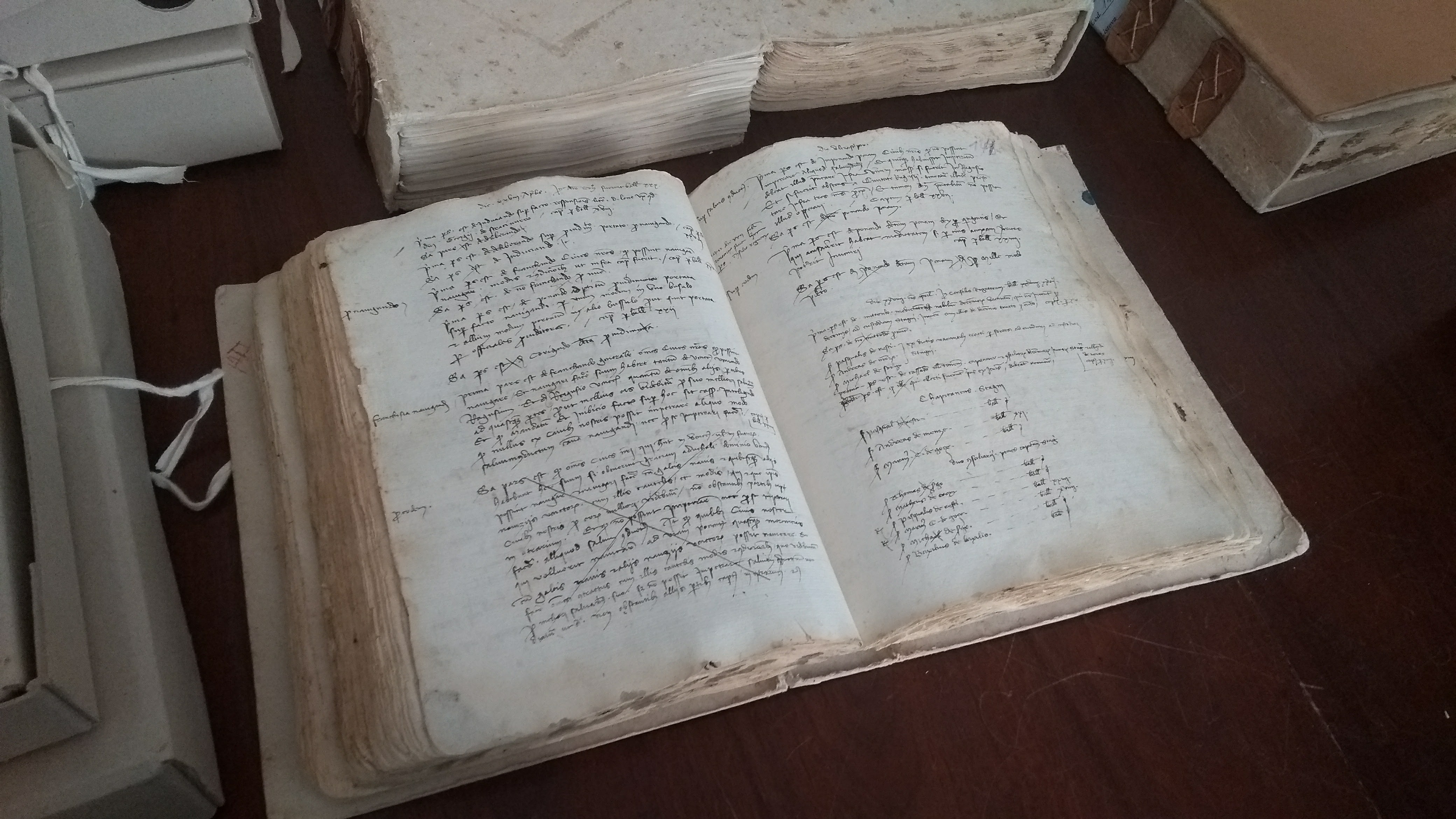

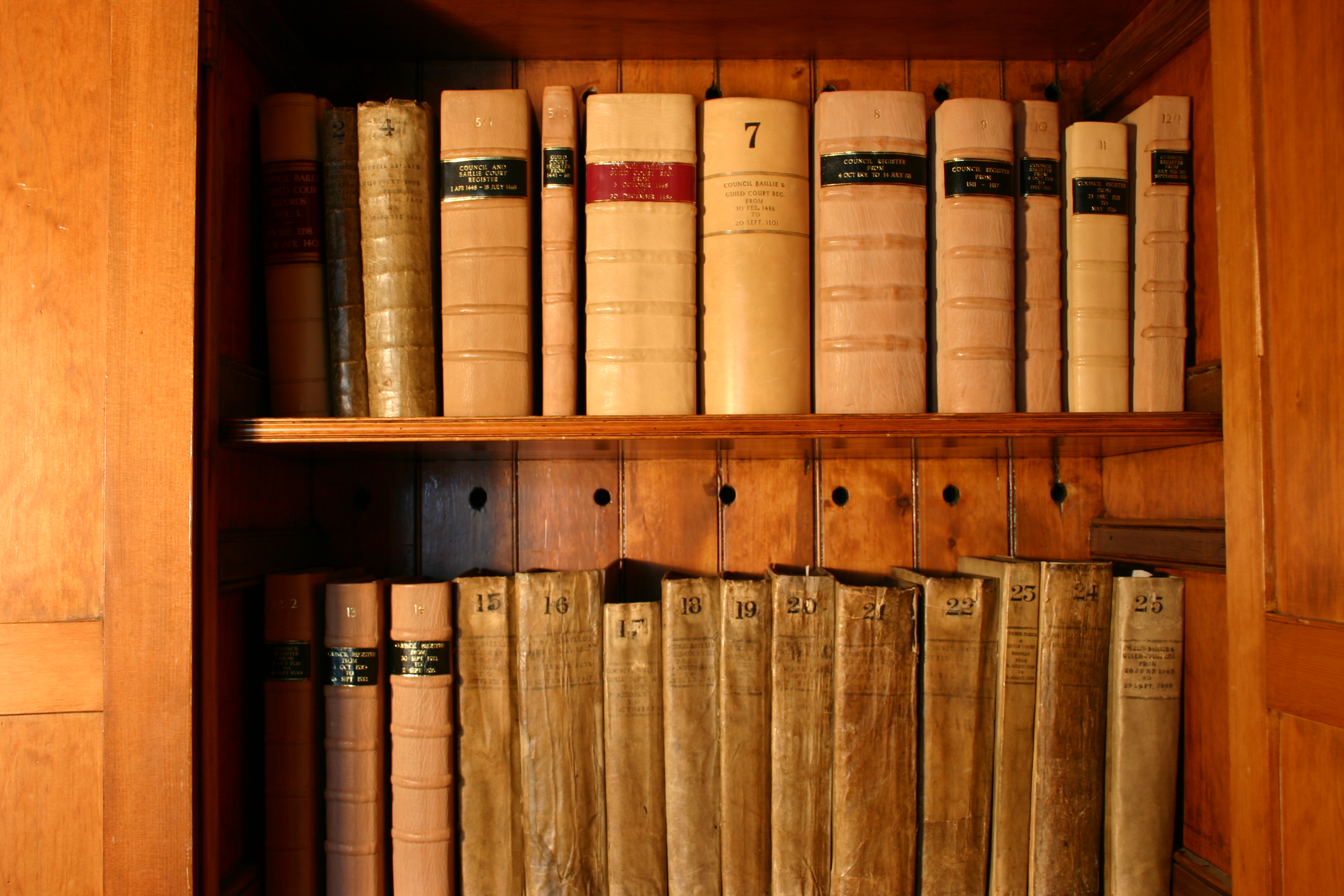

What is it? The Working List tabulates information about the surviving Aberdeen Carmelite charters, listed chronologically. For instance, it records that in 1399 for a charter by which William Crab donated land to the Carmelites, the witnesses included the provost, Adam de Benyn, and twelve other named men. It also records that the seals of William Crab, and of two bailies of the burgh (Simon de Benyn and William Blyndcele) were attached to the charter. This work helps to identify activities of burgh officials and other prominent figures, including in the period from c.1414–c.1433 when there is a gap in the main council register series.

The charters listed here are from the Marischal College Archives, part of the University of Aberdeen’s Special Collections. The Marischal collection in part contains the charters of the Carmelites, or Whitefriars, first established in Aberdeen in 1273.

Two sample transcriptions of charters are included, one in the Middle Scots vernacular, which records a grant in 1421 by Elizabeth Gordon of Gordon, who was the mother of the first earl of Huntly. She made her own gift and also confirmed “ye gift of my lady my eldmoder [grandmother] dam margret of keth ye qwilk my eldmoder has gifin to my said bretheris [the friars] of before tyme gone“.

The charters concerned have some playful illuminations, including that of a cockerel, shown above, and the head of a crowned king in a charter of David II, and intertwined fish, shown below.

Where is it? The Working List is available under a Creative Commons licence on the OSF (Open Science Framework), at https://osf.io/rdsfg/. Its long title is Working List of Witnesses and Authentication of Carmelite Charters, Aberdeen: Held in the Marischal College Archives (University of Aberdeen Museums and Special Collections), version 1.0, https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/rdsfg

licenced under CC By 4.0.

Where does it come from? The Working List began as the appendix created by Julia Vallius for her Senior Honours Dissertation entitled ‘Textual identities and urban communities: Understanding the role of charters and burgh records in the formation and creation of community identities, using the Aberdeen Carmelites charters as a case study’ (April 2020), supervised by Jackson Armstrong. Julia’s dissertation won the Kathleen Edwards Prize in Medieval History. Julia is currently undertaking a PhD in Medieval History at the University of Glasgow.

Julia and Jackson have worked over time to compile a first version of the Working List of Witnesses. Future versions can update, extend and augment this resource. Julia and Jackson are grateful for the support of the Museums and Special Collections throughout this project.

Working List DOI link [ https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/rdsfg ]