Regular readers of this blog will know that the focus of the Law in the Aberdeen Council Registers project are the eight registers that span the period 1398-1511. Yet the earliest record of council business anywhere in Scotland also resides at the Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire Archives and is known as the Burgh Court Roll. Predating the first surviving Register by some 81 years, it dates from 1317.

17/11/17 City Archivist , Phil Astley (blue shirt) with Lord Provost Barney Crockett and Dr Jackson Armstrong. Courtesy of Aberdeen City Council.

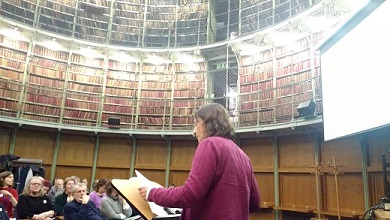

Being great lovers of birthday cake, the project team couldn’t let the roll’s 700th anniversary go by without a suitable celebration for this nationally important document, so on Monday 20th November a public talk was held in the Town and County Hall at the Town House in Aberdeen, with City Archivist, Phil Astley introducing fellow project members Dr Jackson Armstrong who provided an overview of the project and Dr Andrew Simpson who spoke about the context and content of the roll itself.

The Burgh Court Roll is a rather unusual looking item, markedly different to the volumes that we are working on. At around 160cm long and 20cm wide, it comprises five panels of parchment that were stitched together when it was created, including a brieve, a letter issued in the name of Robert the Bruce, which has been sewn to the main roll about half way along its length.

At some point in the nineteenth century, a small tube had been fashioned to accommodate the roll and, apart from those occasions when it was removed from the tube to be consulted, it was kept within the tube until 2006. At that time it underwent significant conservation work to repair a number of holes that had appeared over time and to “relax” and flatten it. We know that in the later sixteenth century there were more of these rolls in existence….”evil to be read”. Why has this particular one survived? The town clerk in 1591, one Mr Thomas Molisone, undertook an inventory of the burgh records and found various old books, leaves, and scrolls in a poor state of decay. He appears to have preserved only the surviving Burgh Court Roll as an exemplar from before the time of the first ‘buik’ dating from 1398.

The 1317 Burgh Court Roll covers a number of cases that came before the burgh’s head and bailie courts between August and October of that year. It has recently been translated from Latin to modern English by Andrew Simpson and Jackson Armstrong.

At the November 20th event, Andrew Simpson concentrated on one of these cases, presenting the narrative through the eyes of a seventeen-year-old Aberdonian woman who features in the first case. The dispute was heard between 1316 and 1317, and the young woman’s name was Ada.

While Ada had been brought up from infancy in Aberdeen, having been born at Martinmas in the year 1299, at some point her family had left the burgh to live in “another part of the kingdom”. But now, following the death of a close relative, Ada returned to her native town, in order to assert her rights of inheritance in a toft (i.e. a piece of land) and a tenement (i.e. a building) in the Gallowgate.

The trouble was that that land was currently held by an influential man, William of Lindsay, Rector of Ayr who had formerly served Robert the Bruce as Chamberlain of Scotland. The Chamberlain was responsible for overseeing the administration of law and order in the burghs, and the collection of customs and taxes due from the burghs to the king. So Ada’s adversary was not only powerful, but also, presumably, well-versed in the laws of the burghs. The case is a complex and fascinating one, shedding light not only on the legal procedures of the time and where these took place, but on how the fall-out from the Wars of Independence had an impact on the lives of individuals living or connected with Aberdeen. William of Lindsay had a claim to the property because he had been granted it by King Robert. But Ada’s claim was through an ancestor who had taken a loan from one Roginald of Buchan, for which they property had been given in security. Roginald had been forfeited by King Robert for his support for the Comyns against the king. King Robert had then granted the property to William of Lindsay. Later, following the victory at Bannockburn, Roginald had sought to return to the king’s peace. A problem thus arose when the king restored to Roginald all his former lands and possessions, including the property in the Gallowgate.

As Dr Simpson showed, ultimately, Ada secured a payment from William of Lindsay in return for transferring the lands to him. Ada declared her wish to do so at three head courts of the burgh. This procedure publicised her intentions, giving her kin ample opportunity to come forward to redeem the lands.

The court held by the bailies then convened in the open air at the site of the property and there Ada gave sasine (formal conveyance of the land) to William by the symbolic measure of presenting him with “hasp and staple” – a “staple” being a metal loop that held in place a “hasp” or catch on which, for example, a door might hang. The bailie received a denarius de uttoll from Ada, and from William a denarius de intoll. The denarius – penny – of intoll was a payment given to the bailie when someone was put into burgh land. Likewise, the penny of uttoll was paid on quitting burgh land.

The story of the seventeen-year-old Ada and her successful attempt to assert her hereditary rights in the Gallowgate somehow captures the imagination. That the Burgh Court Roll can reveal such fascinating glimpses into life in Scotland’s deep past is reason alone to celebrate its 700th year.

Written by Phil Astley, with Jackson Armstrong and Andrew Simpson.