On Friday 30 September the ‘Law in the Aberdeen Council Registers’ (LACR) project team was joined by members of the public at the Maritime Museum in Aberdeen for an interactive presentation on ‘Piracy, plunder and shipwreck’ and aspects of the LACR project. The presentation was part of Explorathon ‘16 or European Researchers’ Night, an event staged on the same day in university cities throughout Europe.

The audience was welcomed by Chris Croly, Public Engagement Officer at the University of Aberdeen and one of the organisers of the Aberdeen Explorathon. Jackson Armstrong then introduced the Aberdeen registers, highlighting their importance as a source for the history of Aberdeen and its hinterland, and for its relations with the rest of Scotland and trading partners abroad. In the first section of the presentation Edda Frankot focussed in more detail on Aberdeen in its European context. Using a number of examples from the records themselves, Aberdeen’s role in late medieval piracy, plunder and shipwreck was illustrated. It appeared that the city did not prosecute any of its citizens that were active in capturing ships from other regions in northwestern Europe. One reason may have been that the men involved were the shipmasters and merchants (and at least one provost, Robert Davidson, and one admiral, the earl of Mar) who were also in charge of the city’s government and courts. But more important was perhaps the fact that the capture of the ships was most likely not considered to be piracy, but justified acts as part of maritime warfare, or as part of attempts to regain compensation for losses sustained abroad.1 During the presentation the members of the public present were quizzed on aspects of the subject of piracy, plunder and shipwreck and asked to vote on one of two answers. As the photo shows, the audience soon caught on to the line of questioning…

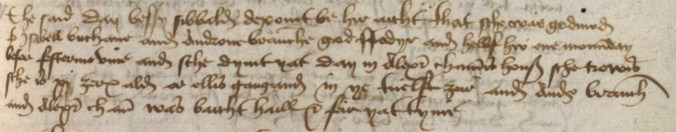

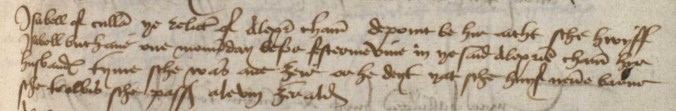

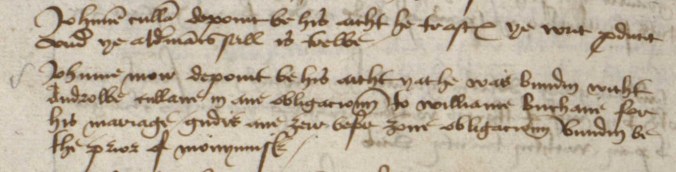

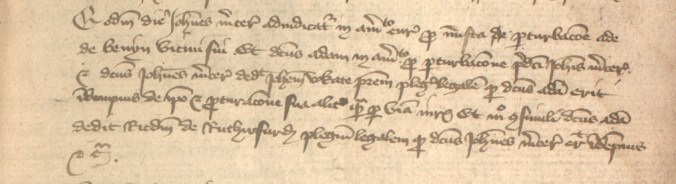

The second part of the presentation focussed on aspects of the LACR project. William Hepburn explained how the transcription process works and what difficulties can be encountered when transcribing fifteenth-century urban registers. The audience was also asked to try to read some words from the records, which proved quite difficult. Anna Havinga then turned the audience’s attention to linguistic aspects of the Aberdeen records, especially the bilingualism of the clerks who wrote the entries in the manuscripts. She then challenged the audience to link up words in old Scots with their modern English counterparts.

This short quiz ended with a plea for help to identify the meaning of a word that the project team had been unable to find. People were asked to send us their solutions via twitter, facebook or email. The word in question appears in a number of entries on the payment for a large number of barrels of this item of merchandise imported from Zeeland in the Netherlands: ‘iggownis’.2 Eventually, the best suggestion was given by Lucy Dean, who responded to a second appeal for help on facebook on 3 October: onions. This word is usually spelled with ‘ing-’ in Middle Scots, which is why we had been unable to locate it in the Dictionary of the Scottish Language (http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/ing3oun ). This exercise just shows how useful crowdsourcing can be: there is a great community of people out there with a very large combined knowledge. Thank you to everyone who contributed with suggestions!

- With regards to medieval Scottish piracy, see David Ditchburn, ‘Piracy and war at sea in late medieval Scotland’, in: T.C. Smout (ed.), Scotland and the Sea (Edinburgh 1992), 35-58 and ‘The pirate, the policeman and the pantomime star: Aberdeen’s alternative economy in the early fifteenth century’, Northern Scotland 12 (1992), 19-34. For the early modern period, see Steve Murdoch, The Terror of the Seas? Scottish Maritime Warfare, 1513-1713 (Leiden and Boston 2010). ↩

- ACR, vol. 5, pp. 358, 359, 361 (12, 14, 16 March and 2 April 1459). ↩

The port of Aberdeen in the later fifteenth century was not nearly as busy as it is today. Exactly how many ships docked at the medieval quays in an average year is unknown, but in the first half of the fifteenth century less than ten ships sailed abroad in most years.

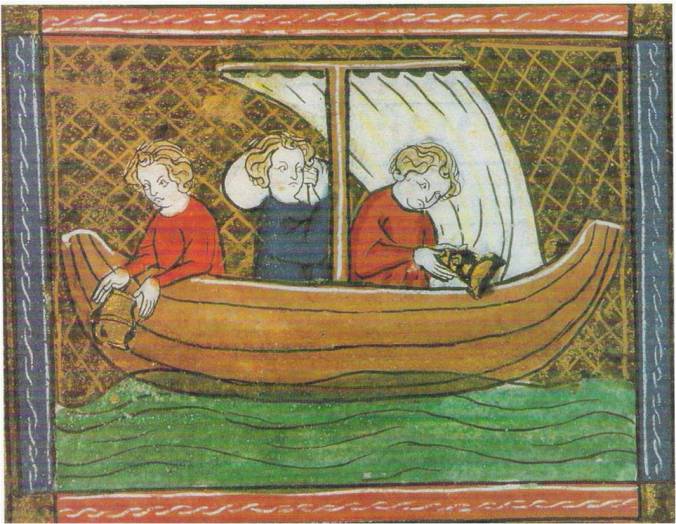

The port of Aberdeen in the later fifteenth century was not nearly as busy as it is today. Exactly how many ships docked at the medieval quays in an average year is unknown, but in the first half of the fifteenth century less than ten ships sailed abroad in most years. The assize decided that Walter, a merchant whose goods had been cast overboard, presumably in order to save the ship in an emergency situation, though this is not specifically stated, would be compensated for his losses. The other merchants would ‘lott’ with him. In addition, the skipper would ‘lott’ with the merchants whose goods had been cast with either his ship or his freight. To lot means to contribute a proportionate share to a common payment. This was the usual way in which the sacrifice made at sea to save the whole vessel, its goods and its passengers (in legal terminology: general average) was compensated in most of northern Europe in this period (with some variation). It is also in accordance with the Rôles d’Oléron. These medieval sea laws which originated in France appear to have been valid in Scotland, as several copies of a translation into Scots have survived as part of collections of the main Scottish laws.

The assize decided that Walter, a merchant whose goods had been cast overboard, presumably in order to save the ship in an emergency situation, though this is not specifically stated, would be compensated for his losses. The other merchants would ‘lott’ with him. In addition, the skipper would ‘lott’ with the merchants whose goods had been cast with either his ship or his freight. To lot means to contribute a proportionate share to a common payment. This was the usual way in which the sacrifice made at sea to save the whole vessel, its goods and its passengers (in legal terminology: general average) was compensated in most of northern Europe in this period (with some variation). It is also in accordance with the Rôles d’Oléron. These medieval sea laws which originated in France appear to have been valid in Scotland, as several copies of a translation into Scots have survived as part of collections of the main Scottish laws.