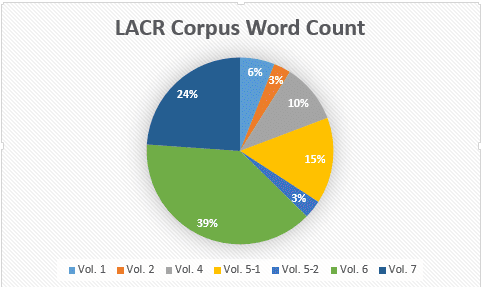

by Edda Frankot

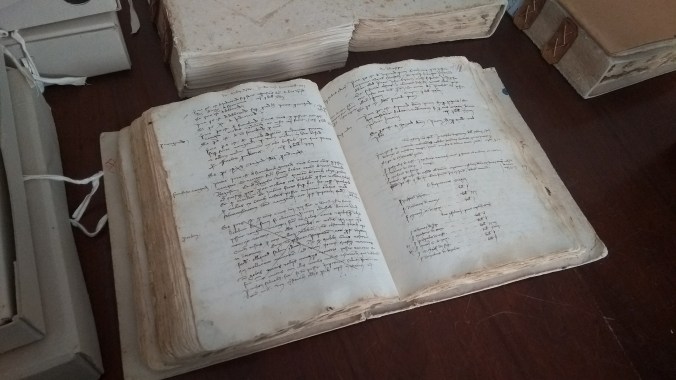

The medieval magistrates of Aberdeen, like their modern counterparts, were concerned with the accessibility and cleanliness of its roads, with building regulations and with potentially hazardous sites. Unlike the modern city council, however, the medieval government only had a small amount of staff working for it permanently or on an annual basis, such as clerks, sergeants and a bellman. For other tasks adhoc committees or officials were appointed. But there may also have been others doing duties which remain largely invisible in the sources as they have survived, because these duties were not directly relevant to the court, unlike those mentioned above. The only aspects worthy of noting were their appointment and any financial arrangements.

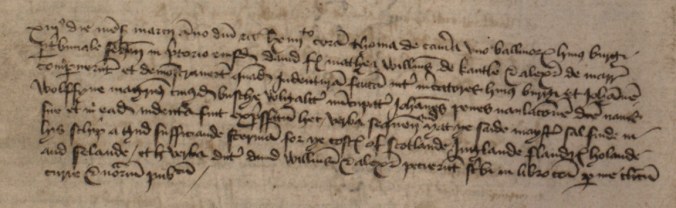

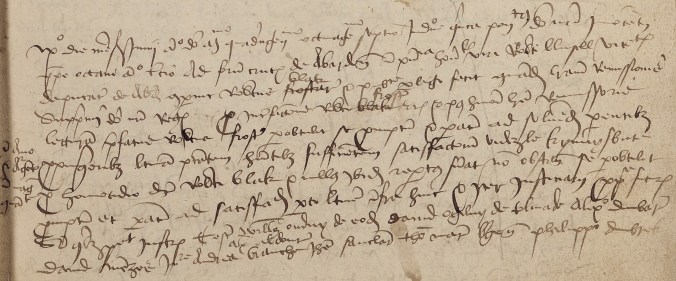

In 1479, for example, the alderman, council and community hired Alexander Coutts to mend the causeways and gutters of the town and to keep all the streets clean so that ‘al men may haf honest and clene passage throuch al the toune’. He would be paid by the people of Aberdeen as follows: all owners of houses with a fireplace (‘fyre house’) would pay him a penny. All other ‘outburgesses’, ‘inburgesses’ (that is to say burgesses living outwith and within the bounds of the town respectively) and ‘indwellers’ (non-burgesses) who had a chamber or a house would also pay a penny, half of them at Martinmass (11 November), the other half at Whitsunday.1

ACR, 6, pp. 599-600.

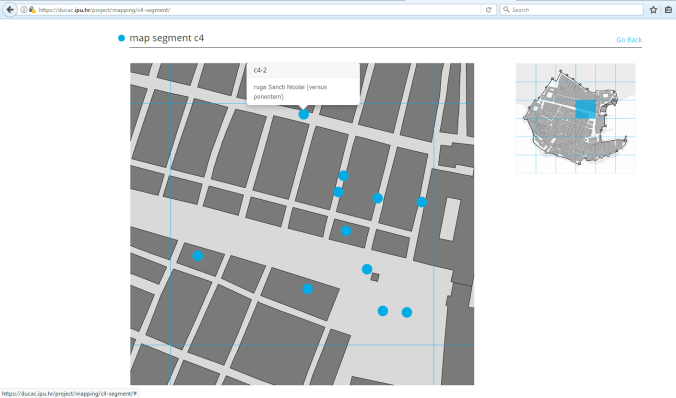

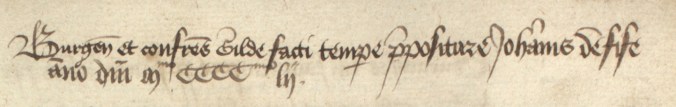

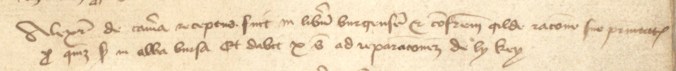

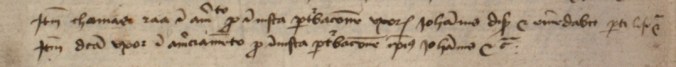

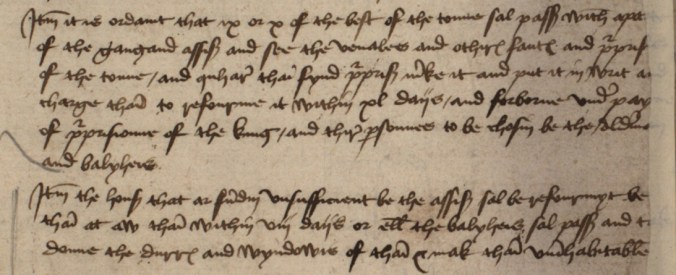

An adhoc committee of 9 or 10 ‘of the best of the town’ was to be appointed by the alderman and baillies in 1449 to go round the streets with the ‘gangand assize’2 to investigate any ‘purprisioun’ or purpresture, that is to say the ‘illegal enclosure or encroachment upon the land or property of another’, often on public or common land.3 Wherever there was any such encroachment, they were to make note of it and charge whoever was responsible to rectify the problem within forty days.4 This exercise resembles a perambulation. The fact that any failure to comply takes place under ‘pain of purprisioune of the king’ also suggests that public property is the focus of the action, which was also the case in perambulations. Different from other known perambulations is the absence of the rest of the population when doing the ambulating and the route followed. This seems to have been a check of encroachments along the streets of Aberdeen’s inner city, rather than along the inner or outer march stones, which were further out.

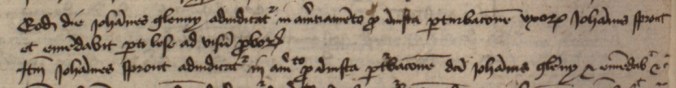

ACR, 5-1, p. 34.

The assize was also to check whether houses were safe. If any were found to be ‘unsufficient’, the owners would be allowed only eight days to repair them. Otherwise the baillies would come and take down the doors and windows and make the place uninhabitable.5 In the case of houses in disrepair, the town magistrates thus took a rather abrupt approach. This may have done wonders in getting those buildings repaired quickly by owners who could afford to get workmen out to do the job. But it would be a disastrous policy for landlords (and/or anyone living in their houses) who could not act so swiftly for whatever reason. There is no further evidence whether such people could receive a deferral if requested.

These three entries show that the town magistrates cared about the cleanliness and safety of Aberdeen’s streets and buildings and organised the maintenance and oversight of it, though based on these three entries it is difficult to say how regular this was. The town government was also concerned about any encroachments on public property and so they organised checks of this. This is a fact already well known from the history of the perambulations, or ‘riding of the marches’, though most of the information we have about this is post-medieval.6 As such, these entries form a useful addition to our knowledge of local government in the later Middle Ages.

- ACR, 6, p. 599-600 (13 Sep 1479). ↩

- It is not entirely clear what the gangand assize is. It would make sense if the nine or ten men chosen would make up this assize, but the way it is phrased these men are to go with the assize. ↩

- ‘Purprestur(e n.’, Dictionary of the Scots Language (2004) Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd. Accessed 2 Mar 2018 <http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/purpresture> ↩

- ACR, 5-1, p. 34 (c. 15 Feb 1449). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See for example: The Freedom Lands and Marches of Aberdeen, 1319-1929 (Aberdeen 1929). This includes a map of the inner and outer marches perambulation routes. A recent sample check of the registers from the 1630s-60s has shown that the list of ‘References in Council Registers to Perambulations of the Marches’ (Appendix V, p. 35) is not in any way complete. ↩